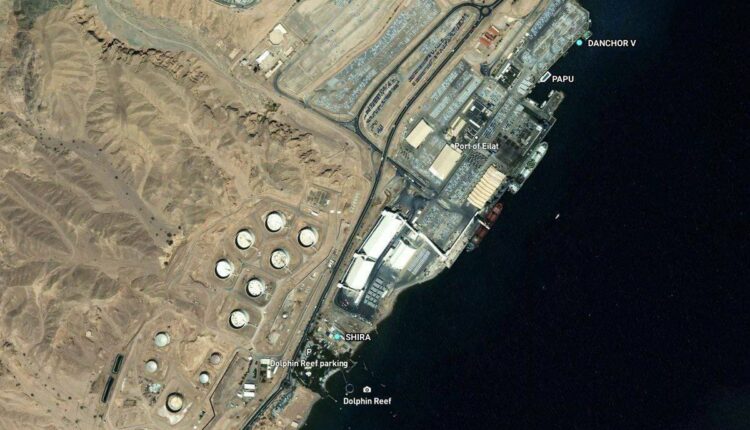

It didn’t survive the battle… Eilat port stuck under the weight of the strategic impacts of the Yemeni naval blockade

Derar Al-Tayeb – Al-Khabar Al-Yemeni:

The Yemeni operations in support of Gaza stopped with the ceasefire, but that changed nothing for the port of occupied Umm Al-Rashrash (Eilat), which has returned to the forefront of the scene within the enemy entity in recent days as an intractable crisis and a witness to a major strategic change made by Yemen. Restarting this high-importance Israeli infrastructure now requires regional and international movement (from the Israeli perspective), or at least an economically unviable plan aimed only at showing a kind of “non-surrender” to the Yemeni naval blockade, whose impacts have clearly transcended the economic field.

According to its CEO, Gideon Golber, the port administration recently contacted the American embassy in Israel, as well as the Egyptians, Chinese, and Emiratis, to support the resumption of the port’s activity by exerting regional pressure leading to the lifting of the naval blockade imposed by the Yemeni Armed Forces on Israeli navigation in the region, as clarified by the “Calcalist” newspaper.

The Hebrew newspaper “Hayom” reported that the port administration also sent urgent messages to the finance, economy, and transport ministers of the enemy entity and to the head of the Knesset Finance Committee, requesting immediate intervention, warning that it would be forced to close completely and lay off more employees if there was no clear government action within weeks.

The administration said, “The southern port of the State of Israel can no longer bear the burden alone. It is not just about business profitability but about preserving a strategic national asset and a vital source of employment for the residents of Eilat and the Arava Valley.”

It is unclear what the responses of the Americans and Arabs were to the port administration’s communications, but the Knesset Finance Committee held an emergency meeting to discuss the port’s situation. Apart from the port’s Chairman of the Board, Avi Hormaru, acknowledging during the session losses of about 200 million shekels (over $60 million), there was nothing new or a result different from previous meetings.

On the Knesset’s table is a proposal previously submitted by the port administration to “force” ships coming from the Mediterranean to transit the Suez Canal and unload vehicles at Eilat Port—a process that incurs additional costs initially estimated at $800,000 but that have now risen to $1.2 million per ship, with the government paying half this cost, with the port and importers sharing the other half.

The Eilat Port administration justifies this plan as necessary “to create an image of victory,” a justification that acknowledges the plan’s economic inefficiency. Elad Burshan, an Israeli expert in customs and international shipping, explains that “routing ships through the Suez Canal lengthens the navigation route, increasing not only the cost of canal transit but also the time spent using the ship, crew expenses, insurance, and fuel—all costs ultimately borne by the consumer,” considering that “any attempt to impose Eilat as a discharge destination by artificially altering global trade routes is illogical.”

He added, “In fact, this plan encourages an unnecessary extension of the route and the payment of unnecessary transit fees that will be transferred from the state treasury to the Egyptian state treasury for using the Suez Canal,” confirming that “the scheme itself is misleading; it talks about splitting the cost between the state, importers, and Eilat Port, but practically, none of them actually bears the cost. In the end, everything is passed on to the consumer. Furthermore, every dollar added to the transport cost adds additional taxes, as import duties are calculated based on the total transaction value, including transport, and this means that artificially increasing transport prices means doubled and unnecessary taxes, which will directly affect the cost of living for all Israelis.”

However, the issue has transcended economic considerations. The port administration’s talk about the need to create an “image of victory” stems from the reality of the strategic damage represented by the port’s closure as a southern gateway for the enemy entity, linked to calculations broader than mere financial profit and loss figures.

The Hebrew newspaper “Hayom” says that “for Eilat, this is no longer just an operational matter; it is a focused political effort seeking to return the Red Sea to its proper course,” and that “the government’s decision, whether to restore the port’s strategic status or abandon it, will not only affect the future of the port but also the economic future of Eilat as a whole.”

For this reason, representatives of the Ministry of Economy in the enemy entity do not oppose paying money to return ships to the port via the Suez Canal, but they oppose issuing an order requiring importers to compulsorily unload ships in the port, arguing that it “harms competition,” and instead propose operating a navigation path agreed upon with the Israeli company (ZIM) and the Italian company (Grimaldi) to transport vehicles to the port.

Meanwhile, there is significant disagreement among representatives of the Finance, Transport, and Economy ministries regarding studying these proposals and who bears the responsibility for pursuing them. This frustrates Eilat Mayor Eli Lankri, who sees these discussions as “entrenching the status quo,” adding, “The port is currently in debt for over 10 million shekels, and as mayor, I don’t know how to deal with a deficit of this amount.”

Nevertheless, “Hayom” believes the issue has transcended the limits of financial pressures, incentives, or the proposals on the table, because “the entire system has learned to bypass the southern port, and when the entire supply chain relies on a new and efficient model, it becomes extremely difficult to revert it, and even if the Red Sea opens and insurance is reduced, Eilat will not be the natural stop for cars coming from the East, as the market has managed to handle the situation without it, and perhaps even better.”

It is considered that “the chances of Eilat Port returning to its role as a major player in the vehicle transport market are slim, not because ships will stop arriving, but because the rules of the maritime industry changed long ago, and the recent crisis has made them more complex.”

Perhaps for this reason, the Israeli shipping sector has not yet received any clarification regarding the port’s status, despite previous assurances that the ceasefire would be accompanied by a resumption of shipping traffic from the East to Eilat, according to a high-level source in the sector who spoke to the “Globes” newspaper, which noted that “Chinese car shipping companies have gradually begun returning to transporting cars to Europe via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal over the past two months, but they are not currently stopping directly at Israeli ports.”

The change brought about by the Yemeni naval blockade on Israeli navigation was not simple or short-term; it was strategic to the extent that the ceasefire was not enough to restore the port’s activity. This aligns with other strategic impacts associated with this blockade, such as the defeat of the US Navy and its expulsion from the Red Sea and the establishment of a new and influential sanctions regime on the ruins of a hegemony that lasted for decades over one of the most important waterways in the world.